|

Leigh House was built during the years 1590 - 1610 by Robert Henley, High Sheriff of Somerset. It was through Robert Henley and his first wife Anne Truebodie that the house descended in an unbroken line of Henley ownership until the house and its estates were sold by Henry Cornish Henley in 1919 .

The house was then bought with 196 acres for just under £20,000 by Sir George Davies, Member of Parliament for Yeovil and vice-chamberlain to the Royal Household at Buckingham Palace, who lived there until 1949 when owing to pressing financial constraints he was forced to sell. Sir George sold to a Mr. Lawley (whose fortune derived from the noted china shop of the same name in London's Regent Street) who added the tennis court,

currently under restoration, lived there for four years and then sold up in 1953 when the Spillers of Chard took over the reins (Spillers daughter

Jose now lives behind Leigh House. Her husband Graham and son Mike run Leigh House Farm, whose acreage surrounds the house.)

The Spillers sold the house after eighteen months, having originally bought the estate solely for the farmland, to a Mr. Dodderell who, having purchased, immediately advertised the house for sale in the Sunday Times, with a view to dividing it up.

Eventually, in 1954, the house was successfully split into four sections, thus creating a precedent for the future safety of a vast number of country houses the length and breadth of England which have since been rescued from the Bulldozer and the uncaring profiteer through conversion into smaller residential units or country hotels or uniquely in Leigh's case a combination of the two.

Leigh House,c.1900

The construction of Leigh House spanned two periods of British architecture, Elizabethan and Jacobean, but the house is strictly Elizabethan in style; the opening fifteen years of James I's reign (1603 - 1618) saw little or no

Architectural innovation, although the arrival of Dutch gables, pilasters and heavy ornamentation was just around the corner.

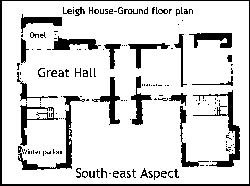

Floor plan c.1990

|

Leigh House is built to the traditional Elizabethan E-plan, two wings and a slightly less prominent centre projection, and is constructed of sawn

redstone, a local form of sandstone, under a slate roof. (There are other fine local examples of the Elizabethan manor in the E-plan at Montacute and Barrington

Court. Externally the house has changed little over almost four centuries and indeed when viewed from the parkland it looks much the same today during the reign of Elizabeth II as it would have done during the reign of Elizabeth

I.

|

The house was completed in 1610, at a time when the first British settlers were establishing the colony of Virginia across the Atlantic, and up to the present day has only seen two external alterations, both of them additions: the extension to the rear of the west wing, very much in keeping with the rest of Leigh House and built in 1931 (despite the

date stone 1672), and the Victorian quarters annexed to the east wing and used to accommodate the growing number of ancillaries needed to keep a house of such exacting grandeur in the manner accustomed.

The land surrounding Leigh House has also changed little other than in ownership, with the formal garden, walled rose-garden and parkland girdled by a ha-ha, still in evidence.

A tour of the inside of the house follows but first, to bring the whole story of Leigh House into focus, a brief excursion into its prehistory.

In 1066 the manors of Street and Leigh were given by William the Conqueror to his fellow countryman the Baron de Mohun as reward for having served at the Battle of Hastings with such gallantry (the parish of Winsham was originally divided into two tithings of which Street and Leigh comprised twenty-one houses and a gentleman's seat.)

In fact William bestowed no fewer than fifty-five manors in Somerset alone on this distinguished lord who fixed his chief residence at Dunster Castle

.

During the early part of the thirteenth century the land on and surrounding the present site of Leigh House was transferred to the Henley family and apart from a brief sequestration during the years 1551 - 1588 when the land passed from the Henleys to Brother Busske, a kinsman of the Bishop of Bristol, the manor of Leigh remained in Henley hands until 1919, a period of some 750 years. 1988 celebrates the 400th anniversary of Robert Henley reclaiming his

rightful inheritance.

The word Leigh is a modern form of the Anglo-Saxon word 'leah', pasture land. The original house, Leigh Grange, a thatched farm building, was erected on the pasture for the convenience of neighbouring Forde Abbey to which it was monastically tied.

After the Reformation it was burnt down and the house standing today was built on the site. There is every reason to believe that to this day a tunnel still links Leigh House to Forde Abbey, although to be strictly accurate the tunnel would have connected Leigh Grange to the Abbey, hence the difficulty in marking its exact location.

The tunnel would be in all probability not have been the only one

exiting the Abbey and providing means of escape for the monks in

residence there who were coming under increasing royal persecution in

the mid-sixteenth century.

Behind the new symmetrical facade the house interior differed little From the style of the late Middle Ages - witness the two bay medieval windows.

Were you to have been one of Robert Henley's first houseguests the immediate impression upon entering Leigh House would have been one of untrammeled

space. The Hall would have opened out to left and right filling the centre part of the house, thus dividing the servants' from the master's quarters.

The Hall had a multitude of purposes, it was the servants' dining and common-room and was occasionally used by the gentry for feasts and

plays; also Leigh House being a little small to boast its own chapel, the Hall would have been used to hold prayers.

Of the two courtyards front and back the rear courtyard would have been connected to the kitchen and offices again in line with medieval thinking.

Back inside, the primary room downstairs would have been the oak parlour, which quite possibly started life as a

bedroom. But the main room at Leigh, the ceremonial pivot of the house, would have been the great chamber upstairs; also called the dining-chamber this magnificent room would have been used to entertain lavishly and overeat nobly, masques would have been enacted, in fact it would have been difficult to say for sure which enhanced which to a greater degree - the room or the occasion it played host to.

Leading off from the great chamber was a withdrawing-room for after dinner mints, not necessarily a bedroom although this was to become increasingly likely.

Aside from the new extension the other sleeping quarters would have changed little.

The Henley estates were acquired at a time England was forcing back her frontiers almost daily. Two of Robert Henley's west country neighbours and contemporaries, Francis Drake and Walter Raleigh were returning from the Americas laden with immense wealth and a number of Henleys were quick to style themselves "merchant venturers." Whilst some of this wealth would have been presented as tribute to their Queen, much would have found its way west, if it had not already been dropped off on the voyage to London. Such untraceable impedimenta had a habit of moving fast and free in high circles.

More probably though it should be remembered that after the Reformation England saw the greatest redistribution of land and attendant wealth ever seen on these shores; vast tracts of land, entire communities that had been held by the Church or those closely affiliated to it were seized and then disposed of at will over subsequent decades, some justly earned and fairly bought, others granted as a gift on the execution of some royal caprice. The trough was wide and full and the few that could come to table ate well.

To explain away the disappearance of such trappings is no easy task either, although the waning of the Henley fiscal star coincides with the taking of a house in London's Hanover Square and all the entertainment and temptations that would have

entailed. The Henleys were famed for their relentless pursuit of illegitimate children, doubtless a pleasurable enough diversion in the short term, but in the final reckoning a formidable drain on the family purse if a certain standard of respectability was to be maintained at their level of society.

So much is certain, but the top floor of the house is still a matter for some conjecture. The author though puts his head on the block and says this area would have housed the ultimate in seventeenth century

modernity: the entire top floor would have been given over to a Long Gallery. Pointers to this are the quality of the upper rooms, the false door and artificial floor level. The Gallery would have been used to display commissioned works of art, probably family portraits, and was used as an exercise room in the unlikely event of bad British weather! Mainly though at that time it was a pure testament to one's status; rather like owning an exotic pet, the conception of the idea is quite thrilling but what on earth does one do with a post-pubescent crocodile?

A copy of this picture hangs to-day over the main staircase. It

was painted in 1773,and portrays a member of the Henley family

dressed as Chinese noble

youth. |

The Georgian Henleys were clearly happy with the endeavours of their forebears, changes were small, gradual and in keeping with the times. By 1850 an inventory of the house shows the order we maintain today, eating quarters downstairs, sleeping on the upper

floors. The original Hall had gone giving way to a Great Hall and Breakfast Room. Upstairs the Great Chamber housed a snooker-table and above that the Gallery was long gone making way for extra servants' quarters. If the Henley fortunes were on the wane Leigh House would be the last to feel the

pinch .

|

.Someone once said that when it came to country houses, progress meant standing still. Perhaps at Leigh House it even means taking a step or two back in time.

Following the successes of William the Conqueror in 1066, Britain played host to an influx of foreign merchants and entrepreneurs keen to make their fortunes and open up new prospects for themselves.

One such man was Johann De Henle De Henle who arrived at the beginning of the twelfth century and settled in the West country. It was a part of England the Henleys were not to forsake for a further eight hundred years.

The early Henleys do not appear to have been voracious amassers of land preferring instead the pursuit of religious or military endeavours. They married quietly into respectable local families accumulating a modest but constant stream of dowries into the family.

The bulk of the Henley estates in Somerset, Devon and Dorset were acquired

by Robert Henley between 1576 - 1613 and aside from the construction of Leigh House included the former Forde Abbey estates of the manor of Street and Leigh in Winsham as well as the manors of Colway and the manors of Werringstone and Raplinghayes, Sowells and Wrestalls (Devon.)

Other purchases included the manor of Champernhayes, Wootton Fitzpaine from the Trevelyan family in 1684.

The Henleys also held leasehold property in the manor of Winsham including the parsonage barn and tithes under the Dean of Wells (several lengthy disputes over these tithes in the 17th and 18th centuries have led to an interesting group of papers at the Records Office, Taunton.)

The bulk of the Henley chattels were sold off in 1919 along with Leigh House but the family portraits and silver were saved and are now housed at Crossrigg Hall in Cumbria, home of Henry Cornish Torbock and his brother Commander Richard Henley Torbock, sole grandsons of Henry Cornish Henley who sold Leigh House.

These estates descended intact through Robert Henley, creaking occasionally at the seams during the eighteenth century when there were several instances of receivers being appointed to take rents and profits to pay off family debts, particularly so in the 1770's and 1780's with Henry Cornish Henley's estate.

Such debts as were incurred were however largely offset by the marriage in 1752 of Henry Henley to Susanna Hoste which led to the acquisition of the Sandringham estate in Norfolk. This remained in the family until its sale in 1836 to Spencer Cowper who in the mid 1840's sold on to Queen Victoria establishing the estate as the royal residence it is today.

Later in the eighteenth century problems mounted in number and gravity and large parts of the Henley estate were mortgaged to Thomas E. Clark of Chard. The break-up of the estate began with the sale of Maiden Newton in 1830, with Leigh House remaining the centre of the estate until its sale in 1919 by Henry Cornish Henley. He left no male heir and his sole daughter Florence married into the Torbeck family from Cumbria and subsequently moved north.

Today sadly finds the Henley family thin on the ground. A couple of white hunters in Africa and a smattering of cousins are all that remain of this once ubiquitous family. Perhaps their legacy and heir is Leigh House.

With the recent acquisition of the central section of the house Ray Dale-Smith has managed to centralise the feel of Leigh House once again and give back to all rooms the stature they merit.

The central hall is now perfectly balanced with the Great Hall off to the left and Morning-Room to the right, whilst the Great Chamber upstairs has been returned to its original splendour. Former meaningless cul-de-sacs are now bright hall-ways pointing the way to impressive rooms as was always intended.

The Leigh House of the 1980's has stepped forward once more by looking back.

Leigh House epitomises all that pleases and exasperates about the English persona: at times agonisingly slow to yield its secrets, modest and unspoiled, a house without brazen youth or infirm old age.

Its inhabitants from the earliest times have succeeded in sidestepping religious or political controversy (with the exception of the unfortunate Henley hung, drawn and quartered as previously described, and that a miscarriage of justice on the Grand Scale.) The ambiguous result of this prudence is plain to see: a house untouched by disaster and starved of written records, the spawn of melodrama.

The feeling is one of a slowly fusing warmth; even the ghost, reputed to haunt the upper levels, is said to be benign and not averse to a little idle gossip. Perhaps it might offer this chronicler his best avenue of research were it not for the phantom's apparent penchant for the fairer sex. If contact is made ladies, please don't keep any trysts to yourselves.

The tragic story of Betty Hoight(Hoyt)

Without doubt one of the strangest episodes concerns the true story of Betty Hoyt (my thanks here especially to the Reverend Bill May, member of the Society for Psychical Research and the British Society of Dowsers, still living just a mile from Leigh House.)

In the year 1539 a young servant girl named Betty Hoyt was brought to Leigh Grange, as it then was, by the lady in

residence. At that time Forde Abbey had recently been suppressed by Henry VIII who scattered the monks, forcing them to seek secular work in the neighbourhood. One of them arrived on the doorstep of Leigh Grange, was welcomed in and proceeded to put Betty Hoyt "in the family way."To Betty's mind the monk could only do the decent thing, so she confronted him and asked him to marry her. He refused and to demonstrate her displeasure she murdered him. The ensuing scandal and her ladyship's fear of the subsequent publicity is not hard to imagine.

Betty Hoyt was found guilty, hanged and buried at the small triangle of grass opposite the Lodge House at the end of the rear drive.

It was to this exact spot that the Reverend Bill May was drawn by his pendulum and prayer-book some 440 years later having no prior knowledge of the story of Betty Hoyt. He immediately recognised an area of intense "psychic contamination."

The final words of this story are Bill May's:

"I am sure it was no accident I was directed away so strangely from the other site which 1 was investigating and drawn to the small grass triangle outside Leigh Lodge. All life is purposive. Environmental memories can be retained by places that have been exposed to strong emotional reactions and communicated telepathically to people who are acutely sensitive to such radiations. We must remember that there is mind in all matter, even in plants and soil and stones, as some distinguished scientists have averred.

"'Grid ref. 352052' is mentally alive, retaining memories of the past. When I pass that place I pray for Betty Hoyt and the man she killed which is possibly a reason why I was diverted to it and brought to study its history.

"My prayers there, and yours also, may well be in accord with the Divine purpose and aid the "departed" in a manner unknown to us."

The area, including Leigh House, is now declared to be cleansed."

Buried Treasure

If Leigh House were an atoll then the reef surrounding it would be composed in no small part of buried treasure. Stories of coins from all

ages coming to light under the blow of spade or garden fork are legion.

Unfortunately the combination of a penurious labourer, absentee landlord and an unspecified quantity of gold, does not always provide for a trouble-free ride as the following letter will illustrate: (at this time the Henleys also had a London residence in Hanover Square.)

Winsham, July 3 1831.

Honoured Sir,

I am sorry to be a very burden to you but I hope you will please to excuse me. My name is George Long and was in company with others digging in your garden at the time

the gold was found and was close by the side of Guppy when he dug it up and we agreed all together that whatever your Honour may be pleased to give us should be equally divided among the whole.

We asked the favour of Mr. Birfield to let us have one piece each to keep in remembrance but as soon as we heard you would have the whole 1 readily gave mine up. Mr. Birfield offered me 20 sovereigns for my part if I would accept it but I thought if he could do so your Honour could. He has been informing me at different times you was expected down week after week but not finding it correct was the cause of my writing. 1 have understood that Isaac Guppy received five pounds which I think should have been divided as I assure you sir I am a poor labourer with

a wife and four small children all depending on my small earnings and 1 dug away the ground while they were employed picking it up.

If you are any way dubious that I had no concern in it I can testify it by producing a note from Mr. Birfield's hand stating the number of pieces I picked up and I might a great many more was it not for that my time was employed clearing away the earth.

I dare say your Honour will know me when I inform you that I made a Violin with my knife and I have another made for your Honour's inspection when you come down which I sincerely hope will be shortly. If your Honour thinks proper to write to Mr. Cooper (House caretaker) or any creditable man in the Parish respecting it I should be glad. Hoping your Honour will consider my present circumstances and comfort me under them in the wish of honoured service.

Yr. humbled servant,

George Long. Bridge.

(The original letter, to be found at Taunton Records Office, immaculately written, would have been dictated by George Long to a professional scribe.)

Mr. Birfield, landlord of the now defunct Knapp Inn at Bridge was without doubt a man possessed of admirably acute 20/20 vision when it came to pinpointing the gleam of gold at Leigh. Six years prior to the above discovery he had unearthed 300 Charles I gold pieces from beneath the roots of a laburnum tree in the gardens.

The Henley family's predilection for

tranquillity and the low profile took a nasty jolt in the late seventeenth century.

The Rye House Plot of 1683 was a manifestly unsuccessful attempt to change the course of British politics.A scheme by a group of Conservative peers to kidnap or kill the then monarch diaries II was betrayed; those implicated were rounded up and executed or fled abroad. Amongst those accused of complicity was Robert Henley who protested his innocence long and loud, to no avail. He was hung, drawn, quartered then promptly found to be innocent. Meanwhile, a bona fide conspirator, the Duke of Monmouth, fled abroad nurturing an equally ambitious scheme.

Robert Henley, who was executed for suspected involvement in

the Rye House Plot |

The Monmouth Rebellion 1685

The Duke of Monmouth was the illegitimate son of Charles II and court mistress Lucy Walter. After Charles' restoration, Monmouth lived at court and the King acknowledged him as his son creating him Duke in 1663 at the age of 14.

When Catholic James II was crowned in 1685 the Duke of Monmouth returned to England from abroad a convinced Protestant fervour would carry him irresistibly to London.

He landed at Lyme Regis and from there progressed through Axminster, Chard and Taunton finally engaging royalist troops at Sedgemoor, the last major battle on English soil. Monmouth was ignominiously routed and captured, taken to London and beheaded.

(It is the custom with all royal progeny for their portraits to be officially commissioned and indeed today you can find a portrait of the Duke in London's National Portrait Gallery. Study it closely.

After Monmouth's execution it was discovered that no painting had been undertaken. The Duke's severed head was forthwith retrieved and placed back upon the unburdened shoulders and the portrait carried out. Note the pale complexion.)

At the time of the rebellion Henley sympathies rested firmly with the Duke, enough for £200 to be donated by the family to his exchequer for carrying his course to Sedgemoor and there is overwhelming evidence to suggest the Duke and his growing number of followers called at Leigh on their journey north in what was obviously a successful attempt to swell their purse.

With this in mind it is a near miracle retribution was not exacted upon the Henley family, for after Sedgemoor James 11 sent Colonel Kirke and one Judge Jeffreys to the west to root out and punish those found guilty of colluding with the rebels.What followed is still regarded as the bloodiest episode in west country history.

Judge Jeffrey's Bloody Assizes have no direct relevance to Leigh House but there is a fund of information on this chilling episode in local libraries, bookshops and museums which all give an unsparing account of Dorset and Somerset's persecution.

Perhaps the only puzzle greater than the disappearance of the Henley fortune is where it came from in the first place. Sheep appears to be the suggestion most often touted but to be able to commandeer vast estates in Devon, Dorset and Somerset including not simply acreage and magnificent houses but entire communities and all on the back of a thriving trade in wool strains credulity, or does it? what are the options?

In view of the Henleys' mounting debts at the time it's a wonder the whole garden wasn't cleared and "tracker Birfield" sent in to root out their salvation.Or maybe they preferred to keep their assets underground. When, in the last century, the Henleys sold off their country seat Colway at Lyme Regis, it was bought by a local butcher on the strength of a rumour the Henley jewels were buried in the grounds. The amount the butcher spent in his attempt to unearth the fabled stones would in itself have probably bought him a far more impressive chest of baubles than the one he never found.

Finally, Leigh House can lay claim to a literary accreditation: in Jane Austen's "Persuasion" it is thinly disguised as the

'red house', a fact confirmed by authoress and Jane Austen aficionado Constance Pilgrim who lived at Leigh House from 1969 - 1981.

Return to top. Click

HERE

Click HERE to return

to Site Map

Click HERE to return to Browse Index

|